Culture, history, heritage and wine

The winery districts represent one of the great heritages of the Denominación de Origen Rioja. According to architect Jesús Marino Pascual, who has conducted a number of studies and written various articles on the subject, and who also coordinated the book entitled ‘Los Barrios de Bodegas. Quel, un ejemplo singular’ (the winery districts. Quel, a unique example), this is both an ethnographic and cultural heritage, given that it is an urban and architectural phenomenon that is closely linked to the specific nature of winegrowing and how it is experienced in a region identified by wine since time immemorial. The winery districts reflect the relationship between the settlements and peoples of La Rioja and wine, grape vine cultivation and the seasonal cycle. Contemporary wineries, as we know them today, are in actual fact a natural progression from the winery districts, moving forward to commercial winemaking and the appearance in the 19th century of the first brands relating to a joint winemaking venture.

///CLICK HERE IF YOU’D LIKE TO FIND OUT MORE

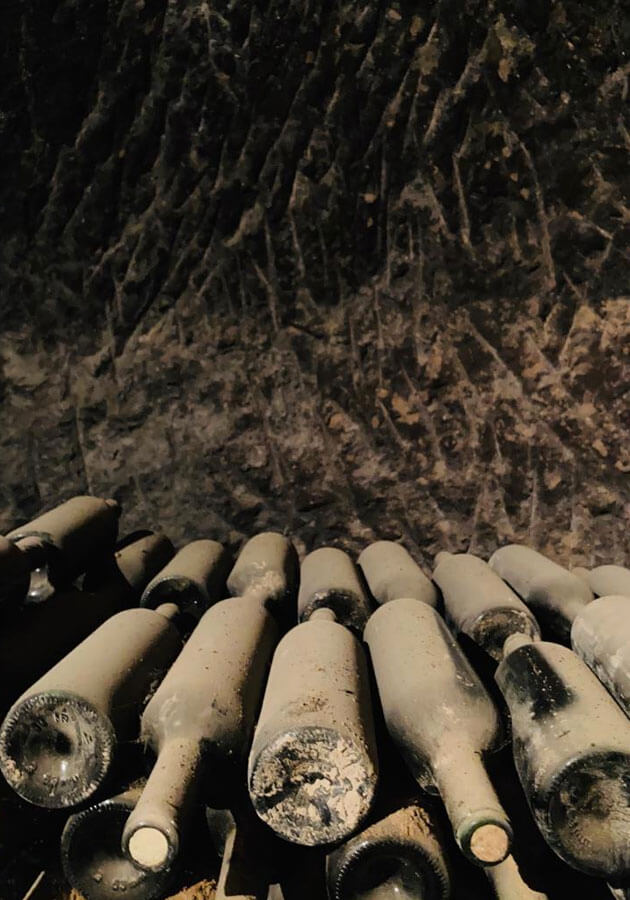

In 2015, the researcher, Elena López Ocón published a doctoral thesis entitled ‘Caracterización de los barrios de bodegas subterráneas de la DOCa Rioja. Estudio y comparación de sus condiciones interiores con las nuevas bodegas comerciales’ (Characterisation of the underground winery districts of DOCa Rioja. A study and comparison of their interior conditions with the new commercial wineries), in which she took an in-depth look at the origins, types of construction and the use of these spaces over the course of history. The author explains that these constructions have their origin in the need to store wine once it had been made, given that in the 8th to 9th centuries wine was made in monasteries or on the estates of great lords. Over time, the farmers adopted these techniques and made wine in the open air, close to the vineyards, in vats carved into the rocks. The remains of some of these vats still exist today, such as the ones located in Sonsierra in La Rioja and, according to the work of Heras and Tojal in 1994, dating back to the 14th and 15th centuries. The grape must obtained was taken to the underground cellars in animal skins and other containers such as barrels, where it was left to ferment in wooden barrels.

In Rioja Baja, evidence of the stone vats used in this primitive winemaking process can still be seen today. As Rosa Aurora Luezas Pascual explained in her article “Historia del vino de Rioja” (History of wine in Rioja) published in the Belezos periodical, «the vats carved in the rock were used to tread-press the grapes, making it possible to make the grape must right next to the vineyards, as can be seen in Alto de la Senda del Convento, San Andrés and San Polite in San Vicente de la Sonsierra, El Portillo, Camino de las Arenas and Santa Ana y Cadalso in Ábalos, Las Gobas in Ribas de Tereso. These structures are also evident in Rioja Baja, such as the rock-carved vat of the Cogote de las Pilas in Arnedillo».

As an interesting detail of this latter structure, of particular note is the presence of a cave facing south-east. Its purpose is not precisely known, although historians speculate that it could well have been a hermit’s shelter.

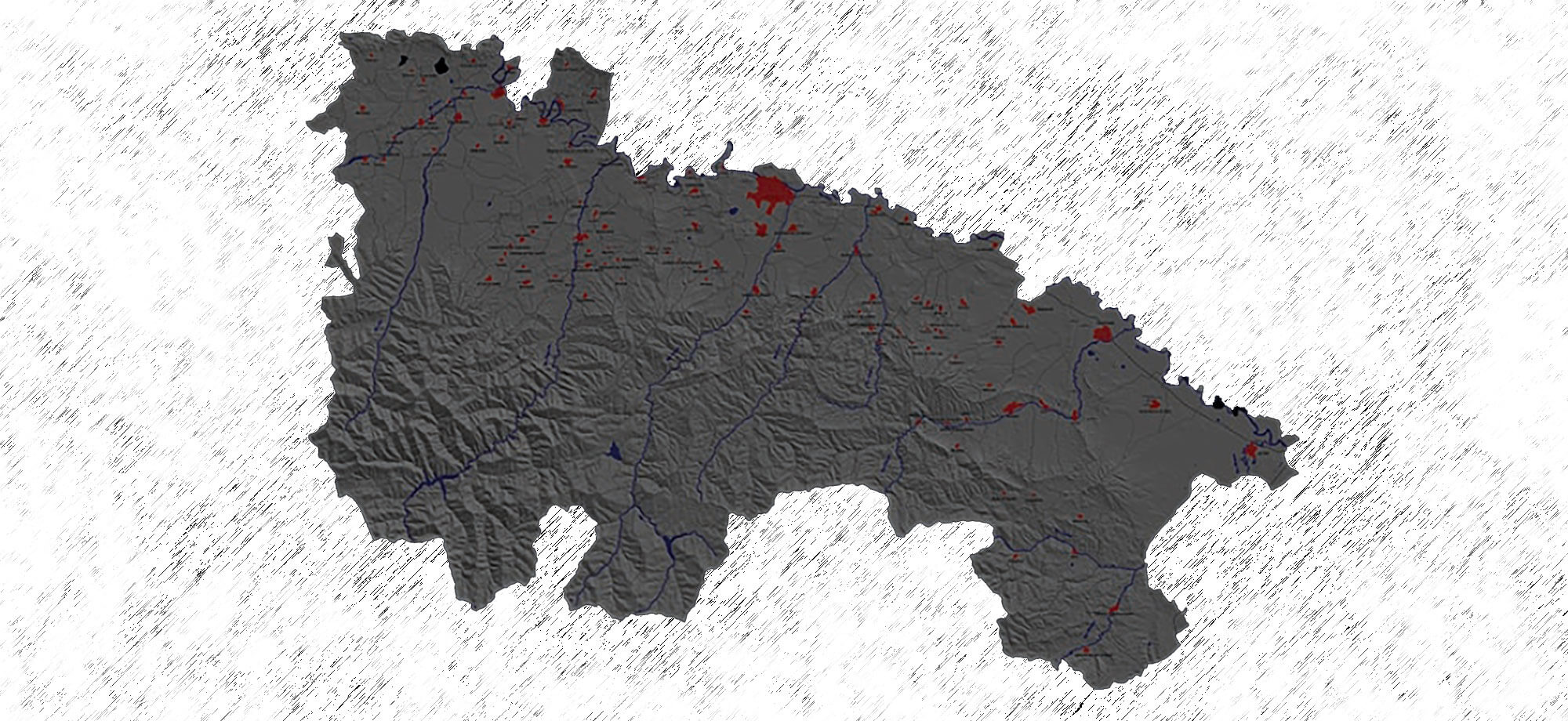

A common feature of winery districts is that they all house underground cellars, most of which have been excavated in slopes due to the orography of the Ebro Valley. However, as a result of the fact that they are organic urban structures adapted to the medium, their typology varies according to area and settlement, depending on the topography and geology of the specific area in which they are located: Ebro basin and other confluent valleys in Rioja Alta, Rioja Media and Rioja Baja, as indicated by the architect, Marta Palacios, in an article entitled ‘Los barrios de bodegas tradicionales de La Rioja’ (the traditional winery districts of La Rioja), published in issue number 167 of the Rioja periodical of social sciences and humanities, ‘Berceo’.

Marta Palacios underscores the fact that those wineries that were not located in the actual town centre under the houses , as in the case of Quel, were excavated in hillocks or slopes close to the towns. This was done for a number of reasons, such as the benefit of locating the winemaking activity at a distance from the residential areas, the typology of softer ground for ease of excavation, the convenience of locating the wineries in places with good accessibility and with a suitable orientation and position for the conservation of wine. This latter advantage became a need in the second half of the 19th century when, due to the boom in grape growing, wineries were much in demand and there was a considerable need to construct new ones. The matter of ownership was a further reason for excavating the wineries on slopes and hillocks, given that this land was generally barren and owned by the municipality, and it was assigned by the town councils to those inhabitants requesting it.

The author of the article explains that these districts are considered to be urban complexes given that «due to their size, they act as either a break with, or complement to the natural environment, even managing to fade into the surroundings» such as those districts that are either set apart, isolated or located on hills. Examples include San Vicente de la Sonsierra, Medrano or Entrena, which appear to be part of the natural surroundings. With regard to most of the districts, their size is either concealed or adapts to the natural milieu, while those buildings that stand above the ground manage to blend into the built environment in a chameleon-like way. In these settings, the wineries remain practically anonymous, except to the locals, who are familiar with the very heart of their towns, such as Logroño, Cenicero and small localities such as Villarroya, and know that these spaces are concealed under their homes.

The author goes on to explain that the exterior architecture forming the streets and paths of the winery districts is generally small scale, with the exception of those towns in which the wineries are part of the urban centre and have been excavated under either the residential buildings, manor houses and even churches such as the case of the parish church of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción in Briñas. However, despite their small scale, the construction traditions of La Rioja are represented in the building of the wineries and underground cellars. These are differentiated by area and reflect the progress of the construction systems used in each period, right up to today.

Marta Palacios expands on the connection between the traditional winery districts and the viticultural spririt present in the towns and villages in which the districts are located, given the fact that they are the result of a subsistence economy and the reflection of a structure of agricultural smallholdings. Huetz de Lemps described the close link between winegrowing and smallholdings in Alto Ebro. This relationship can be observed today in the progressively greater size of holdings, towns and municipalities as one travels down the Ebro river basin in La Rioja.

Right from the outset, the existence of smallholders has been a distinguishing feature of La Rioja, as reflected in the analysis of the records made by tax inspectors, revealing the fragmentation of vineyards and wineries. Based on the Cadastre records for the period 1860-1990, the figures analysed on the social structure of farmers in La Rioja in the late 19th century and early 20th century indicate that two-thirds of small farmers were wage earners and held no farming property and, moreover, not all owners were self-sufficient and able to live off their land.

The exterior architecture making up the streets and paths of the winery districts is generally small scale and, as Marta Palacios explained «with the exception of those towns in which the wineries are pat of the urban centre and have been excavated under either the residential buildings, manor houses and even churches such as the case of the parish church of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción in Briñas. However, despite their small scale, the construction traditions of La Rioja are represented in the building of the wineries and underground cellars. These are differentiated by area and reflect the progress of the construction systems used in each period, right up to today». And the investigator draws the following conclusion: «The architecture of the traditional wineries has no name or surname, but it is identifiable with a time and place, given that it is the fruit of a more or less spontaneous collective activity in response to the need to make and store wine, with buildings that are in line with the surrounding area and its characteristics».

In an article in the Diario La Rioja daily newspaper the journalist, Maria Casado, listed an inventory of this type of construction in the region: «This richness is supported by the following figures: 128 winery districts, distributed in 89 municipalities – in almost half of the 174 settlements in La Rioja – and in almost one hundred urban centres. All this is based on the study ‘Barrios de Bodegas tradicionales de La Rioja’ (traditional winery districts of La Rioja) conducted in 2011 by the architect, Marta Palacios, through a grant from the Association of Architects of La Rioja (COAR) and its cultural foundation (FCAR). «And there may be more, some cannot be easily located, either because they go unnoticed or due to their condition», she admits. Of these, almost 60% are the “slope” type, around 28% are on flat land and 12% on a hillock».

The winery

districts

in the Cidacos Valley

María Asunción Antoñanzas Subero and José Manuel Martínez Torrecilla conducted a study published in the rural life periodical ‘Vida Rural’ on the traditional wineries in Santa Eulalia Bajera and Arnedillo, and explained the rapid growth of these constructions in Rioja Baja: «The Cidacos valley, during the period prior to the great wine boom in La Rioja, had vineyards right from the point at which the river enters La rioja, in Enciso y Munilla, up to where it flows into the river Ebro, in Calahorra. Traditional wineries can be found in the old town centre of Calahorra, although very few are still operating; Autol, Quel, in Arnedo, with urban wineries and a winery area around the Cerro San Miguel hillock; Herce, with wineries around the Monte del Salvador hill, Préjano, with urban wineries, and in Santa Eulalia Bajera and Arnedillo». In other words, these constructions were very common in the area of the Denominación de Origen Rioja and have their own specific characteristics.

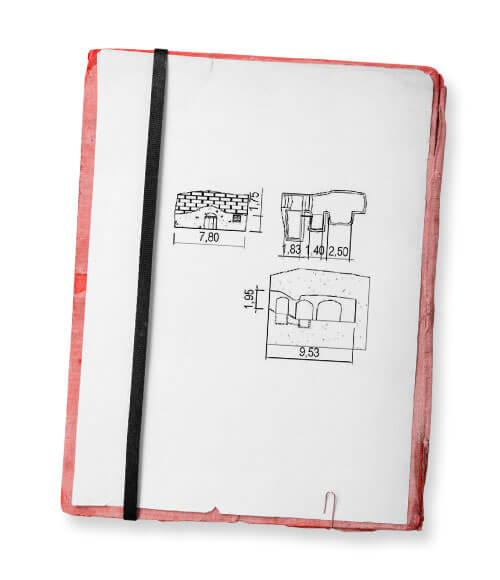

«Traditional wineries in the Cidacos valley adapt to the orography and characteristics of the terrain, which progressively moves from clay materials at the river outlet to other rocky materials, of varying degrees of hardness, along the valley. The type of land would largely determine the excavation process and whether or not there was a need to use pillars and masonry arches. At Santa Eulalia Bajera there is an area of soft sandstones while the substratum at Arnedillo is limestone. The layout of the traditional winery is simple yet effective. In general, the winery comprises a constructed part, the hut, and another excavated part. Normally, the equipment used to extract the wine was located in the constructed part: a stone vat, into which the grapes were emptied for subsequent treading and for the first fermentation, a “torco” or top where the wine was collected, and a press, where the marc or pomace was processed after treading. The underground or excavated part housed the tanks and tubs for fermentation and storage. Based on this general layout, a few variations may be found: the lack of some equipment, such as the vat, press or both, which would be shared by a number of wineries; and a different location of the vats and presses in the underground cellar».

///history

Bodega quarter of Quel

A historical gem

///history

Viticulture in Quel

Earliest origins

///history

Vine cultivation in Quel

The poorest soils for the vineyard

///history

Quel castle

A castle, a stone vat and a winery

///history

Winery districts in La Rioja

Culture, history, heritage and wine