The god Bacchus unfurled his most beautiful rugs on the shores of the Ebro

As the historian Manuel Llano Gorostiza explains in his fantastic work ‘Los vinos de Rioja’ (Induban, 1973), for La Rioja, its wine is its greatest pride and its greatest standard bearer. The god Bacchus unfurled his most beautiful rugs on the shores of the Ebro, between Alfaro and Haro.

However, when wine arrived in La Rioja, it had already been intimately associated with societies regarded as “civilised” for centuries. (Santiago Ibáñez Rodríguez. El tiempo que vio nacer al Rioja. ‘La Rioja, sus viñas y su vino’. Government of La Rioja, 2009). The winemaking tradition of La Rioja began when the region was annexed by the Roman Empire, as was the case in other parts of Spain and all over Europe. The incorporation of wine and vine growing in the lands of what is today La Rioja took several centuries, progressing in line with the stages of the Romanization of the territory. The Romans arrived between the 3rd and 2nd centuries B.C. and the researcher concludes that wine was being consumed from the beginning, first of all by the Romans themselves, then by those who came into contact with them. That wine originally came from the Italian Peninsula and then was replaced by Hispanic wines from the Mediterranean area of Tarraco and Barcino (Laietana).

The route taken by the vines to install themselves in Rioja was different as it required the legal integration of the region in the Empire, the municipalisation of the territory, the introduction of the Roman property system and intensive farming methods. In the middle of the 1st century B.C. systematic cultivation was authorised and commenced in La Rioja and Mediterranean agriculture was introduced through various horticultural crops, fruit orchards, olive trees and grapevines, as well as the necessary techniques for transformation to produce oil and wine, including (as Santiago Ibáñez emphasises) oenology, in order to blend different grape varieties and obtain sweeter wines.

///CLICK HERE IF YOU WANT TO LEARN MORE

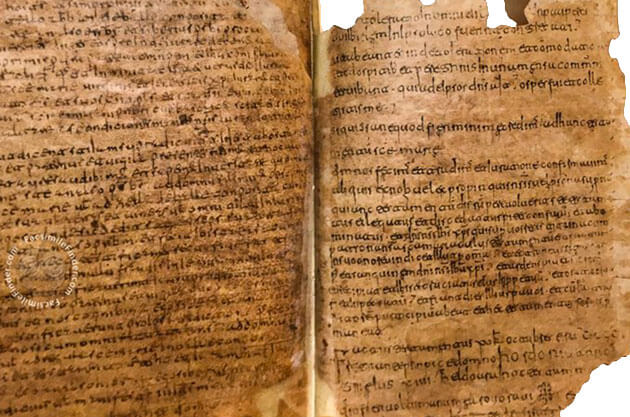

The oldest preserved document that makes reference to the presence of the vine in La Rioja dates from 873. It appears in the Cartulary of San Millán and refers to a donation which features the Monastery of San Andrés de Trepeana. The first evidence of Riojan viticulture is documented in the ‘Charter of the village of Longares’, granted by Don Gómez (Gomesanus), Bishop of Nájera, on 25 July 1063. This establishes a servitude contract in favour of the monastery of San Martín de Albelda, whereby the villagers had to provide «two days ploughing, two days digging, two days labour, two days cutting and one harvesting».

The Camino de Santiago pilgrims route and the big influence of its monasteries had a major significance in the wine culture in La Rioja. So much so that the religious orders were mainly responsible for spreading the winemaking culture. From a series of documentary sources, it has been found that wine was regarded as more than a mere drink, but rather as one of the pillars of the diet of the time. As an example, we can mention the monastic rules for women, transcribed in the year 976 to be observed by the nuns of the Monastery of Saints Nunilo and Alodia, near Nájera, which allowed them to rack off a third of an emina, the daily wine ration for friars established by Saint Benedict.

The vineyards extended around the monasteries and continued to spread out until they covered Navarre, La Rioja, the Duero valley, Lerma, Palencia, the Bierzo and even to the Sil river basin in Galician lands. Wine became a religious symbol of the highest order for Christianity and as a result of the joint actions of the Crown and the monasteries – as Juan Ramón Corpas of the University of Navarra points out, from the 11th century onwards there is a profound transformation of the landscape, with a striking and spectacular increase in the number of vines along the entire Saint James’ Way and the Ebro valley.

The anthropologist Luis Vicente Elías claims that in the case of La Rioja it was the Monastery of San Millán that took charge of organising the local population, in which the first mention of the vines appears in the 10th century and talks about their irrigation. In the 12th century, sixty per cent of the lands cultivated by the monastery were vineyards. The wines these produced were not designed for any kind of commercialisation as they were for consumption in the monastery itself and in the hospices and inns for sharing with the population. Furthermore, the influences of the French religious orders that were following the pilgrims’ route, brought with them both new methods for cultivating the vines and new grape varieties. Throughout Europe the pilgrims´ Camino the relationship of the wines with the monasteries is vital, as they are situated in major winegrowing regions and have developed techniques for making wines of the highest quality which over the years paved the way for many of the most highly prestigious European designations of origin.

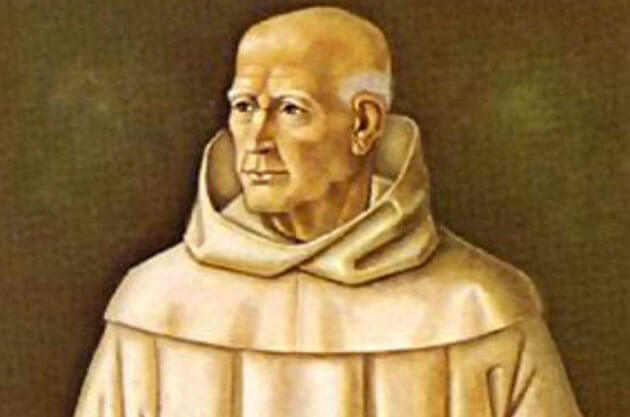

Another of the most significant landmarks in the history of Rioja wine is deeply rotted in the 13th century, when Gonzalo de Berceo, a monk from the Monastery of Suso in San Millán de la Cogolla and the first known poet in the Castilian language, mentions wine in his verses.

Quiero fer una prosa en román paladino,

en cual suele el pueblo fablar con su vezino,

ca non so tan letrado por fer otro latino

bien valdrá, como creo, un vaso de bon vino

I want to write a piece in polished Romance,

in which the people are accustomed to speak to their neighbors,

for I am not learned enough to write one in Latin

it would indeed be worth, as I believe, a glass of good wine.

The permanent concern in La Rioja for the quality of its wines has its roots in the slow evolution over the course of the centuries. One example of this is a bye law ordered by the then Mayor of Logroño in 1635 prohibiting carts and carriages in the streets where the bodegas were located «lest the vibration caused by these vehicles should disturb the musts and prejudice the maturation of our precious wines». The first historical predecessor of the Denominación de Origen Calificada Rioja dates back to the 16th century when, in 1560, the Logroño wine growers chose a symbol that would be proof of the wine’s quality: an anagram corresponding to an interlacing of the initials of the surnames of its members, which was branded onto the wineskins which were transported outside the region. The appearance of powdery mildew, a fungal disease that attacks vine plants, led to a phase of renewal of the wines.

In the second half of the 19th century another disease hit the whole of Europe: the deadly phylloxera. It wiped out the French vineyards in 1867 but was only detected in La Rioja in 1889, so French growers came to what was then known as the province of Logroño in search of Rioja wine in order to make their Bordeaux. By 1880, a large part of the Rioja Alta district, with Haro at the head, has made contact with wine businesses in France, primarily from the Bordeaux region.

However, an apparently infinite demand opened up and in twenty years the land dedicated to vine growing doubled. As the historian Andreas Oestreicher points out, La Rioja was adopting the role of supplier of raw material (grapes and wine) for a foreign industrial sector which transformed it.

Later, against the background of an increasingly more marked French protectionist tendency, the recovery from the plague and the mildew crisis had grave repercussions for the sector in La Rioja: overproduction, a fall in prices and agricultural unemployment. At that point, with the French market shutting its doors on rioja wine for good, making a wine of a certain quality remained the only viable alternative. The time had come for the industrial bodegas to flourish, thanks to the low prices and their ability to impose their criteria in the pricing of the wines.

The accumulation of wealth after those twenty golden years and the absence of French competition, thanks to the Spanish customs measures in response to those of their neighbours, shaped the framework for Rioja winegrowing as the 19th century drew to an end.

And it was in that breeding ground that the dreaded insect brought phylloxera to La Rioja. The plague reduced the vine growing surface area to less than a third in just ten years. Oestreicher states that the only solution to the problem (as the French had done) was to replant all the vineyards using grafts onto American rootstocks, the only ones which were resistant. The introduction of these plants and the setting up of nurseries was met by huge opposition from the Riojan growers, who feared that these might even favour the invasion of the plague spreading to the less affected districts.

On top of that there was the high cost of replanting. They said that it was “a thing and some landowners” suffered attacks from small farmers and labourers, who believed that the replanting would mean the disappearance of their vineyards. There was clearly an underlying class battle going on: «Down with the American vine, bring out the irrigation! », they desperately cried, demanding real solutions for their situation, such as the possibility of switching to another crop through irrigation projects.

Phylloxera took the winemaking sector in La Rioja to two previously unimaginable levels: an unprecedented boom at the beginning and, once the plague hit the region, the greatest crisis in its history. It was at that time that the process of emigration from La Rioja to America began. In 1910 over 20,000 citizens had left in search of a better life in the New World. La Rioja suffered phylloxera in its vines and in its people.

The origin

of the Control Board

In 1892 the laboratory of the Estación de Viticultura y Enología was founded in Haro, where studies were conducted to improve Riojan viticulture and in 1902 a “Royal Order” was published which defined the ‘origin’ for its application to Rioja wines. It was in 1925 that a seal of guarantee of origin was approved as a collective trademark and the Rioja zone was determined. The following year the Control Board of the Designation of Origin was created and this was officially constituted in 1953. On 3 April 1991 Ministerial Order granted “Qualified” status to the Rioja Designation of Origin, the first in Spain to achieve this classification.

Pioneers

del Rioja

The real rise in quality of Rioja began with the introduction of the use of wooden vats, making it possible to give expression to one of the distinguishing features of these wines: their great capacity for ageing. In 1876 Manuel Esteban Quintano had made some early attempts at using these containers after his first trip to Bordeaux, but the great pioneer in barrel ageing was Luciano Murrieta, who after an eventful career in politics and with the rank of Colonel of the Dragoon Guards of the Spanish army, ended up sent into exile in London (1843-1848) as a result of coming out in support of General Espartero. During that period of exile he began to develop the idea of exploiting the winemaking potential of La Rioja because he could not understand why the wine was being used to make mortar, for example. Like anyone who is ahead of their times, he had to put up with a lot of incomprehension, but fortunately Espartero himself and his wife, the Duchess of la Victoria, provided him with their cellars and vineyards so that he could begin to put his dream to test.

His first wines were destined for export and, although one of these first shipments was lost when the ship sank in the Golf of Mexico, the one that reached Cuba did so in perfect condition and earned all kinds of plaudits, giving him the encouragement he needed to found his legendary Castillo de Ygay wine cellar.

For his part, in 1850 Camilo Hurtado de Amézaga, Marquis of Riscal, also decided to back aged wines. During his exile in Bordeaux he became a fan of the wines from the Médoc district and in 1860 had a wine cellar built in Elciego (Álava) with its own vineyards in a quarter of his 200-hectare estate. Over the years, a large number of French experts, headed by Jean Pineau, made their homes in La Rioja, which in the long run marked the start of the history of a wine which today enjoys worldwide fame and recognition.

Words by the master

Néstor Luján

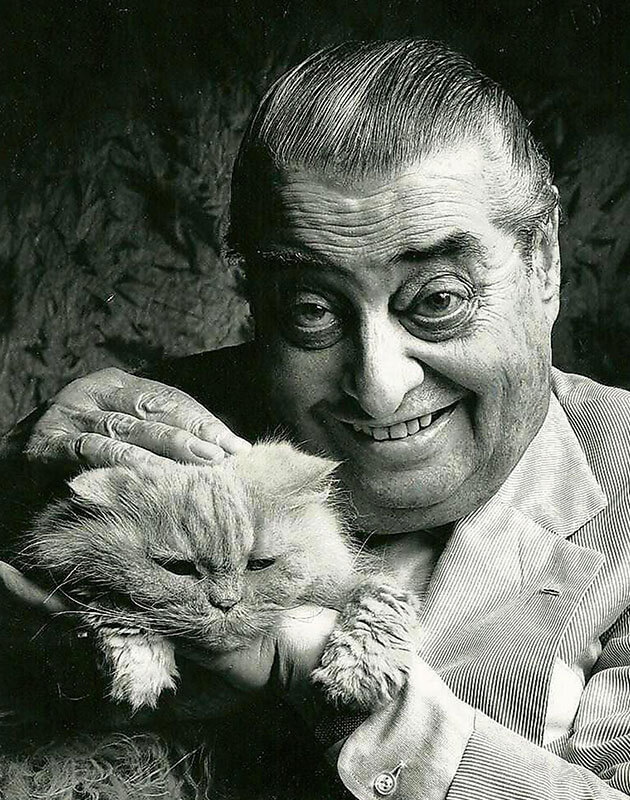

In a campaign by the Control Board in 1985, Néstor Luján defined the producer zones of Rioja wines in these terms: «La Rioja is divided, according to the Board, into three smaller districts or subzones. Rioja Alta has Haro as its capital, the well named cathedral of wine. The land in this district is fairly rugged and the climate is characterised by its abundant rainfall and long, harsh winters; the summers short and baking hot. The Rioja Alavesa, from Haro to Logroño, is south facing. The exposure to the sun makes these wines from the Alavesa thick, alcoholic, low in acidity, with a pronounced aroma and full, dense colour. In the capital of the Rioja Alavesa, Laguardia, we recall having tasted these local musts, vigorous and commanding, very powerful. Finally, we have the Rioja Baja, with Calahorra as its capital. This is also a land bathed by the sun, and the vines in its vineyards, planted along various tributaries of the Ebro –like the Alhama, Cidacos, Leza or Iregua-, produce highly alcoholic wines (…). These wines have deep red colouring, jammy smoothness, low acidity and an exquisite bouquet».

Néstor Luján