A historical

gem

The Barrio de Bodegas, or Bodega Quarter of Quel, dates back to the 18th century and is a real gem. Reference was already made to this district in historical land registers such as those of the Marqués de la Ensenada (1752) and Pascual Madoz (1851), both of which record the existence of more than 350 winemaking caves or cellars in Quel, on a small hillock rising above the southern bank of the river Cidacos.

At present, there are around two hundred underground cellars, forming a strange and complex maze of subterranean passageways and excavations at different levels. All these wineries are in line, featuring a very similar layout: the stone fermentation vat at the entrance, alongside what is locally known as a “torco”, a stone container into which the wine is drained, after treading the grapes. The wineries were also equipped with a press and spaces or recesses in the walls to hold the barrels, which were generally of two sizes: 90 and 200 pitchers. The back of the caves was used as a storage area for barrels and bottles alike.

The advancement of techniques for cultivating the vines and transporting the grapes, led to the adaptation of the “luceras”, the local name for the unusual, original and authentic conduit systems used in Quel to take the grapes from the top of the hillock, where the district stood, to each of the stone vats below. This upper area of the winery district is packed with small constructions, all fitted with a wooden front door to protect the grape reception area.

The entire winemaking process was based on the force of gravity, a system that has now been applied by the Pérez Cuevas family at their new Queirón winery, as the faithful guardian of the identity of Quel, an identity forged by generations of winegrowers and which is now taking another step forward in the quest for quality and purity.

///CLICK HERE IF YOU WANT TO LEARN MORE

El barrio de

bodegas de Quel

un ejemplo singular

Bretón de los Herreros, the Quel-born world-famous playwright, is the author to offer the first overview of Quel’s bodega quarter, and he describes it with outstanding clarity:

«On the opposite bank stands another cliff, parallel to the first one, not as high, but easier to manage and, therefore, at very little cost it has been possible to easily excavate around three hundred cellars, a number that is almost equal to the number of inhabitants, and some of these cellars are extremely spacious. Such is the grape harvest collected in a vast area behind the wineries that it was necessary to found a new settlement, and it is noteworthy that, despite the sufficiency of the place of worship of El Salvador, a medium-sized church with a sad-looking shrine in the field as an annex, there were more temples to Bacchus than in Greece. To visit these places of worship of Dionysus, which many people frequently do, there is an uphill climb, not a long one but, being strenuous, rocky and slippery, it is a worthy rival of the slopes of the Pyrenees or the Alpujarras in Andalucia. It is admirable that no man or beast has ever fallen off the cliff in the upward or downward climb (for reasons that will not be withheld from the reader) and can be considered to be a miracle».

The book ‘Los Barrios de Bodegas. Quel, un ejemplo singular’ (The winery district. Quel, a unique example) is a work of reference that allows readers to discover all about the specific history of the bodega quarter of Quel and will serve as our guide to learn everything about the evolution, history and innermost geography of an area that is related to winegrowing and to the essence of the men and women of this part of La Rioja, since time immemorial. It is, moreover, the cornerstone of the Queirón philosophy.

Manuel Bretón de los Herreros describes the winery district and places it on the southern bank of the river Cidacos as it passes through Quel, in an area known as Las Coronas which, according to previous references, was highly appreciated for its good crop growing characteristics, although the vineyards were planted in much poorer soils. It appears that this outcrop where the wineries were excavated was divided into two areas, although this division has become completely undetectable over time. There is historical evidence of the existence of more wineries downstream in a district known as La Cilla. There were two other winery areas in Quel: on the outskirts of the town, going towards what is now the Calahorra road, and in the town centre itself, located in some of the houses with caves, in the buildings that are closest to the Peña del Castillo, the rocky cliff on which the castle stands. The authors of the book point out that this observation was first documented in the book “Arquitectura popular de La Rioja” (Vernacular architecture of La Rioja) the work of Luis Vicente Elías and Ramón Moncosí de Borbón, published by the Ministry of Public Works in 1978.

In reference to the Land Register of the Marqués de la Ensenada of 1752, cited by Felipe Abad León in his book ‘La Ruta del Cidacos’ (the Route of the River Cidacos), published in Logroño in 1978 by the publishing company Ochoa, the following details were given for the winery district: «Quel had 296 occupied houses in which 338 heads of household lived, with 59 widows and 3 spinsters included in this number. There were also 30 plots of land, which included 8 demolished houses. There were also 4 rural houses and 224 wineries on the outskirts of the town in three districts called Las Coronas, in total the wineries had a volume of 50,000 pitchers».

In 1985 the Association of Surveyors republished the ‘Diccionario Geográfico-Estadístico-Histórico de España’ (Geographical-Statistical-historical Dictionary of Spain) by Pascual Madoz first published in 1851, and which also reported on Quel and its winery district: «Opposite the town, on the other side of the river Cidacos and at a distance of some 700 yardsticks, stands a gentle cliff that runs along the entire right bank of this river from Arnedillo to Autol in which more than 350 caves or cellars have been excavated to store wine». The authors note that the count made by Madoz refers to a surface area of 200 “fanegas” of vineyard, with the “fanega” being the amount of land that can be sown with a bushel of seed, which «we consider to be very little and 11 distilleries with a production of 6,000 pitchers of spirit».

Barco and Elías also looked at the question of the production of spirits in Quel, since according to them «it would be worth the work, given that since 1776 when Juan Delhuyar used to purchase bad wines in that town (as reported by Jesús Palacios Remondo in his book ‘Los Delhuyar’, published by the Regional Ministry for Culture of the Government of La Rioja in 1992), these spirits are mentioned and the contribution of other businessmen. Alaine Huetz de Lemps reported in his book ‘Vignobles et vins du Nord-ouest de L’Espagne’ (Vineyards and wines in northwestern Spain), published by the Geographical Institute of Bordeaux in 1967 that «in 1790, a Catalan from Reus, Mr Josef Revet, established a business in Quel with 6 “boilers” and capable of burning 600 pitchers of wine per hour». Also included is a description of the winery district, copied from Madoz and even the size of some of the wineries: <<They are all similar: along a long passageway, 25 to 30 metres by 4.5 m. wide, niches have been carved out in which the barrels are lodged. Near the entrance are installed the fermentation vats and presses.».

Justiniano García Prado, in an article published in issue number 12 of the magazine Berceo in 1949 entitled ‘Las cuevas habitadas de Arnedo’ (The inhabited caves of Arnedo), describes the winemaking caves of this area that is so unique to La Rioja Oriental: «The nature of the tertiary hillocks and their geological structure makes them ideal for such purposes. A winery district is frequently found in viticultural towns, which are full of bustle in the grape harvesting days and during the characteristic winemaking tasks. The wineries at Quel, Autol and Arnedo and, in general, those in the Cidacos Valley, are of great interest due to their layout and capacity»

The layout

of the wineries

The most common layout of the cave in the traditional wineries of Quel is a horizontal excavation at the same height as the point of access. The interior changes of level indicate successive extensions undertaken over the years. As Barco and Elías explain, all the wineries are in line and all have some very similar maximum widths. Moreover, the construction of the wineries was based on the needs imposed by the actual winemaking process: the fermentation vat was located as close as possible to the winery entrance in order to make it as easy as possible to unload the grapes brought from the vineyard in the traditional round wooden containers known as comportillos.

The larger wineries would have up to two vats, which were generally two metres deep with capacities ranging from 1,000 pitchers (equivalent to 16,000 litres of wine) to 2,000 pitchers. Given that the wineries were located on just one floor, another cavity or well needed to be located very close to the vat. This was known as a “pila” and served to collect the wine drained from the vat and which was then taken to the barrels. These cavities were fitted with their own ladders to reach the “torco” or top, where the wine was collected. The authors explain that this is the reason why the vats at Quel are not as deep as those of other districts in the Rioja Alta, where the wineries generally have two floors.

The press was located close to the vat in a recess of no more than two metres in diameter. During the later years in which the wineries were used, these presses comprised an iron container surrounded by a cage of wooden slats. The flat iron base held a central screw, with a plate at the top which was generally lowered by means of a lever to another plate in order to press the pomace. Given that not all wineries had a press and, therefore, a place to mount a press, the pomace was transferred from one winery to another for pressing purposes. The authors also focussed on the social use of the wineries, given that the area in front of the fermentation vat was used for family gatherings, a place that was sheltered and even had a kitchen and heating, since some caves even had their own smoke flues.

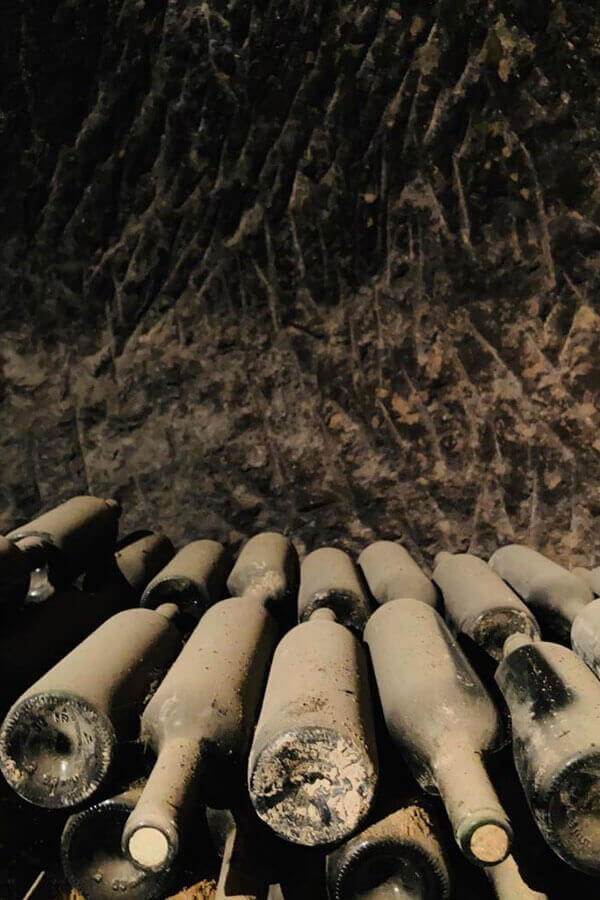

The cave interior had side recesses for the barrels, which were generally of two sizes: 90 and 200 pitchers. The nineteen-thirties onwards were marked by the construction of cement vats, basically in the wineries of those winegrowers who had decided not to form part of the cooperative. The back of the caves was used as a storage area for barrels and bottles alike.

Although the caves of the Quel winery district were created for winemaking and storage purposes, in the sixties a few caves started to engage in mushroom cultivation. However, this activity was not long-lasting given that this sector soon moved to industrial facilities. The authors explained that the wineries were excavated for two reasons: thermal requirements and the characteristics of the land. The climatic conditions of Quel make it necessary to keep the wine thermally insulated and, moreover, the wineries were constructed on north-facing common land in order to keep them cool in summer. Elías and Barco focus on a unique aspect of these constructions, given that these are private places in areas of public use. The first step was to request permission from the Council in order to start the excavation. Thus, in most places in La Rioja, the wineries were not entered in the municipal register, although they were considered to be assignments of property and the ownership of these winery caves passed from one generation to the next.

How was the wine made

at the Quel wineries?

During the wine harvest, the grapes were taken to the winery in wooden containers. There, they were emptied into the fermentation vat with no differentiation between variety or colour. Few white grape varieties were planted in this area of La Rioja: the early white “Temprana” was grown as a table grape while the Moscatel grape was used either for direct consumption or for hanging up to dry in order to produce the sweet “Supurao” wine. The advancement of techniques for cultivating the vines and transporting the grapes, led the wineries to adapt to these new developments, particularly with regard to how the grapes entered the winery after the harvest, with the implementation of “luceras”, the local name for the unusual, original and authentic conduit systems used to take the grapes from the top of the hillock, where the district stood, to the fermentation vats below.

There were two different winemaking processes at the Quel winery: 70 percent red wines, with rosé wines accounting for the rest. Let’s take a look at how the red wines were made: the grapes were emptied into the stone vat and left to ferment for ten to fifteen days. In order to determine whether the process had been completed, the technique was to light a candle and, if it went out, then the grape must was still fermenting. Where possible, a pomace treading process would take place each day in order to break the berries and to facilitate the process. An interesting fact is that, once the fermentation had ended, the wine was left with the pomace for an additional day in order to gain more colour, a maceration technique that is still followed today for smoother extractions of the pigments from the grapes.

The wine was drained through the outlet and was then taken to the barrels in goatskins and, at a later date, by pumping, initially by a manual process and, from the fifties onwards, by electricity. Once the wine had been drained from the vat, the solids were divided in half and the pomace was piled up in order to allow the remaining wine to drain off more easily. The other half was worked in the same way on the following day and the wine so obtained was considered by many to be of the highest quality.

The pomace was put into large baskets and taken to the press where, with a force of 500 kilos, up to eight press loads a day could be made. This pressed pomace was then used to make the spirit drinks and aniseed liqueur, for which Quel is so famous.

The rosé wines were made by macerating the pomace after treading and pressing. The grape must was then left to ferment in the barrels. These wines were of a much deeper colour than the rosés of Rioja Alta. If the desired colour was not achieved, then pomace was added to the barrel (colouring agent) during fermentation. In January the pomace was removed in a single racking process.

The construction

of the wineries

The Quel wineries were excavated during the cold, rainy days of winter when it was impossible to work in the fields. As the story goes, groups of grape harvesters from the San Pedro Manrique and Yanguas areas of Soria, would spend long seasons in Quel, working on the caves or on other normal winter tasks. The work was completely manual (pickaxes, spades, hoes, rods, bores, mallets and chisels), explosives were never used.

The layout of each cave was made by taking the existing caves as a reference. By knocking on the walls, experts were able to determine the precise distance away from the neighbouring cave. Some caves are very close together, however there is still sufficient separation to ensure a fully consistent wall thickness. With regard to the construction period, there are engravings for specific years such as 1788 and 1760, and the caves appear to date back to the 18th century.

In 1947 the San Justo Cooperative was founded with 15 members (although the majority of the growers in Quel subsequently joined it). This meant that the bodega quarter was no longer needed to make wine, although some have still continued to do so right up to this day. At the end of the nineteen-sixties, the vineyards were affected by a great crisis which led to a huge reduction in the area dedicated to vines and to a drop in the number of growers and, therefore, in the use of the traditional wineries of the district.

///history

Bodega quarter of Quel

A historical gem

///history

Viticulture in Quel

Earliest origins

///history

Vine cultivation in Quel

The poorest soils for the vineyard

///history

Quel castle

A castle, a stone vat and a winery

///history

Winery districts in La Rioja

Culture, history, heritage and wine